Is All Stress Bad?

When we hear the word “stress”, we tend to think of it as being a negative thing. Chronic stress can certainly have physical, emotional, and behavioural symptoms and sequelae affecting your health. But stress is the body’s natural response to pressure or demands, and in the short term, it can be extremely motivating, such as finishing a project before a deadline or running away from a dangerous situation.

But “stress” is also used in the strength and conditioning, training, and rehab world with a negative connotation. We hear people say, “don’t do the knee extension machine because it stresses your knees” or “deadlifts put stress on your low back.” While said with good intentions, there is a lot of context missing in these statements. Rather than viewing stress as only bad, we need to look back at the SAID principle to see how stress can be a good thing.

The stress we’re usually referring to in the rehab world is the physical demands we place on our bodies through physical activity. In material science and physics, the mathematical formula for stress is: stress = force / surface area. This formula explains why it is dangerous to step on a single nail but safe to lay on a bed of nails. When stepping on a nail, you have your entire body weight (the force) coming down through your foot onto the pinpoint (surface area) of a nail. But when you lay on a bed of nails, your body weight is displaced over a larger surface area, despite still being sharp nails.

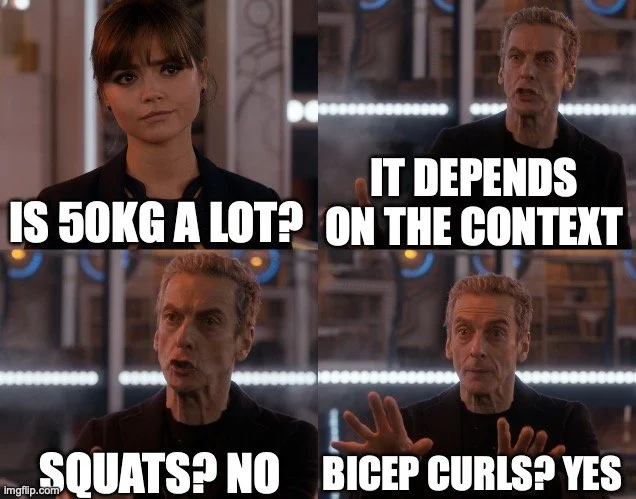

This is usually the context that people use when it comes to stress and exercise. In the above comment about knee extensions stressing the knee, the implied warning is that weight, positioning, and movement from the knee extension machine applied more force over the small knee cap. What is usually offered as a safer alternative is squats, as the movement allows for more muscles and joints to be used to lessen the stress on the knee via a larger surface area.

While mathematically this may be true, it is important to remember that the human body is not a machine and is capable of adaptation. Just like you shouldn’t start your first day of running by doing a marathon, you should be selecting an appropriate weight for the knee extension machine. With time and consistency, you should be able to progress your weight because your body adapts and gets stronger, even if it is more “stressful” than other leg exercises. As well, the human body is highly individualistic. While one person may find the knee extension machine irritating for their knees, someone else may find this perfectly fine and a great quadriceps-isolation exercise. Differences in anatomy, training history, previous injuries, and beliefs are some examples of why an exercise would vary between people.

We can also refer to stress in a more general sense when we think of our training program and physical activities as a whole, and our ability to recover from them. This is where semantics may muddle things, as sometimes stress, load, and volume are used interchangeably when referring to the total amount of physical activity someone is doing. But in reality, when we do physical activity, we are increasing the demands on our cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems, thereby “stressing” them. But this stress is needed, as it is the main driving force for adaptation and improving these systems. If we don’t stress our bodies enough, we don’t see improvements in our function, and we may even regress. If we over-stress our bodies with excessive activity, we’re not allowing for the recovery needed to cause improvements, and we may even be setting ourselves up for injury and burnout.

When we talk about stress in rehab, there needs to be context behind it. Stress is just a number, or rather just the representation of force over surface area - it means nothing without context and is inherently neither good nor bad. Stress, both the colloquial and mathematical meaning, in rehab is necessary for a full recovery. An injured muscle, tendon, ligament, or bone must be loaded and stressed in order to induce physiological adaptations leading to the healing of the tissue with greater strength capabilities if one hopes to return to physical activity pain-free. The timing of this stress and the amount of stress are key though in a rehab program— stressing a tissue too early or too much can certainly cause setbacks, but we also want to make sure we’re not delaying or under-stressing the tissue as this will not set us up for success.

Stress is necessary, but whether it helps or harms depends on how much you can tolerate at the time. Rehab then isn’t about avoiding stress, but about applying the right amount at the right time, based on what the person can tolerate.