If You Throw, You Need A Different Kind of Rehab

Baseball and softball are growing in numbers and visibility in Ireland, especially at the recreational level. Injuries can and still do occur, but sports medicine is understandably built around hurling, Gaelic football and rugby. Throwing in baseball and softball is different. The forces are different. The long-term adaptations are different. Therefore the rehab has to be different too. If you throw, you need someone who understands throwers. Treating a thrower like a general shoulder is misguided.

Baseball and softball are growing in numbers and visibility in Ireland, especially at the recreational level. Injuries can and still do occur, but sports medicine is understandably built around hurling, Gaelic football and rugby. Throwing in baseball and softball is different. The forces are different. The long-term adaptations are different. Therefore the rehab has to be different too. If you throw, you need someone who understands throwers. Treating a thrower like a general shoulder is misguided.

The Hidden Forces of Throwing

Throwing a baseball is one of the most stressful movements in sport, especially for pitchers. At maximum layback, the elbow experiences roughly 60lbs of torque (the equivalent of five bowling balls pulling down on it). At ball release, the shoulder experiences a distractive force of about 1.2 times bodyweight, meaning the joint is resisting forces that are actively trying to pull it apart. All of this happens in less than a second, with the arm rotating at nearly 7,000° per second. These aren’t normal gym demands. Throwing places extreme stress on the shoulder and elbow at speeds and forces most rehab programs never prepare you for. Bands and light dumbbells might help early on, but if rehab never progresses to heavy strength work, eccentrics, plyometrics, medicine balls, and actual throwing, you’re not preparing for competitive throwing. If rehab doesn’t build you for the demands of throwing, it isn’t baseball rehab.

When Abnormal is Actually Normal

Because of the extreme forces involved in throwing, pitchers develop adaptations that don’t look “normal”, and they aren’t supposed to. The problem is that these adaptations are often treated as something to correct. A throwing shoulder is not a general population shoulder.

One of the best examples is humeral retroversion. After years of throwing, especially during youth development, the humerus gradually twists outward. This increases external rotation (ER) and decreases internal rotation (IR). This shift isn’t a flaw. More ER generally means more velocity. It also allows pitchers to achieve layback without over-stressing the front of the shoulder, because part of that motion is coming from bone structure and not just soft tissue laxity. But here’s where misunderstandings happen. A player presents with shoulder pain, IR looks limited, it gets labeled as GIRD (glenohumeral internal rotation deficit), and posterior capsule stretches are prescribed to “restore” the lost IR. Yet when both arms are measured properly, the total arc of motion in the throwing arm should be within about 5–10° of the non-throwing arm. If total arc is preserved, that “loss” of IR is just humeral retroversion — a normal and beneficial adaptation. Trying to aggressively correct that can mean altering the very adaptation that helps performance. This is why comparing a thrower’s shoulder to population norms can be misleading.

Labral findings are another example. Many throwers show labral changes on imaging due to the repetitive “peel-back mechanism” when throwing. However, many remain asymptomatic. Imaging findings alone do not equal dysfunction, especially in throwers. Treating the scan instead of the athlete is misguided. In throwers, the question isn’t “does this look normal?” It’s “is this functional and resilient for the demands of throwing?”

Asymmetry is a Feature, Not a Flaw

Baseball is inherently one-sided. You throw with one arm, you rotate in one direction, you load the same hip and shoulder, over and over again. The body adapts to this repeated stress - that’s the S.A.I.D. principle at work. Over time, throwers become structurally and functionally asymmetrical because the sport demands it. Rehab and strength training often aim for symmetry. Restoring baseline strength after injury is important but it’s in reference to the uninjured side. Perfect symmetry isn’t the goal in baseball; the goal is resilience within the asymmetry. A thrower doesn’t need to look balanced — they need to tolerate the demands of their position. In baseball, functional asymmetry is normal.

Return-to-Throwing is a Skill

Developing a return-to-throwing plan for a baseball or softball player is complex. Most interval throwing programs (ITPs) progress using distance (as a proxy for intensity) and number of throws (volume). This seems logical, but in reality, it’s far messier. Without wearable technology to measure elbow stress, or even a radar gun to monitor velocity, maintaining consistent intensity from session to session is difficult. Distance alone does not equal force as there is no perfectly linear relationship between how far you throw and how much stress is placed on the arm. Two pitchers who both throw 90mph do not necessarily place the same amount of stress on their arm either. Differences in mechanics, timing, strength, and body structure all change the equation. You can throw a short distance with maximal effort. You can throw farther with less effort. And that’s before we even introduce tools like weighted balls, long toss, and pulldowns. These methods may be effective for building arm strength and velocity because they intentionally increase stress on the system to drive adaptation, but they also alter mechanics and increase load. If used incorrectly or layered into a rehab process too early, they can easily set a player back.

Returning to throwing after injury is not just about being pain-free - it’s important but not the same as being ready to throw. Readiness requires: appropriate progression, controlled volume, gradual exposure to higher intensities, adequate recovery, and mechanical awareness. Returning to throwing is a matter of exposure to stress, and if you get the stress wrong, you can experience setbacks.

Specialized, Not Standard

If throwing creates unique adaptations, then our standards for assessment must reflect that. We cannot assess or rehab a thrower’s shoulder the same way we would a non-thrower’s. In general rehab, we often use the uninvolved side as the reference, but a thrower’s dominant arm should not look like their non-dominant arm or like the general population. Throwers often need greater ER strength, specific strength ratios that differ from standard “norms”, and unique endurance demands. If we apply generic shoulder strength standards to a thrower, we risk under-preparing them for the demands of throwing or over-correcting adaptations that are actually beneficial. A thrower’s shoulder isn’t broken because it doesn’t look symmetrical or textbook-normal; it’s specialized and specialized athletes require specialized assessment.

Protecting the Developing Arm

When we think about kids, we tend to imagine they’re indestructible — flexible, resilient, and able to bounce back from anything. Kids are just as susceptible to overuse injuries as adults, but the injuries look different. A common example is Little League Elbow (LLE). This is irritation of the growth plate on the inside of the elbow caused by repetitive throwing stress. In young athletes, the growth plate is the weak link in the arm. That’s why we don’t commonly see 10–14 year olds tearing their ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). The growth plate fails first. Once that plate closes (typically 15–17 years old) the weak link shifts and now the UCL becomes the structure at risk. The stress doesn’t change but rather the tissue that absorbs it does.

LLE is, at its core, an overuse injury and it reflects a broader issue in youth sports: early specialization and year-round competition. The baseball culture of today with travel teams, showcases, and constant exposure can quietly accumulate thousands of throws on a developing arm. This matters, especially when recovery, strength development, and overall athletic diversity are limited. Protecting young throwers isn’t about shutting them down. It’s about: managing throwing volume, respecting recovery, prioritizing long-term development over short-term exposure, and educating coaches and parents on how the throwing arm actually develops. Understanding the throwing shoulder and elbow isn’t just about rehab - it’s about prevention and giving young athletes the chance to keep playing for years to come.

Throwing is what makes baseball and softball unique and it’s also what makes players different to rehab. As the sports continue to grow in Ireland — in numbers, competition, and visibility — the need for informed, sport-specific injury management grows with them. Throwers cannot be assessed, progressed, or returned to play using generic shoulder guidelines. If you throw, you need someone who understands throwers. My role isn’t just to reduce your pain. It’s to understand the demands of your position, your schedule, and your long-term goals. It’s to manage load, guide progression, and prepare your arm for the realities of competition. It’s to return you to the field with confidence, not just clearance, because being pain-free isn’t the same as being ready.

The Activity is the Rehab

The purpose of a rehab plan shouldn't be just to get you out of pain and heal the injured area, but to prepare you to return to your sport or activity feeling confident and ready to go. This is something that is often missing from rehab.

The purpose of a rehab plan shouldn't be just to get you out of pain and heal the injured area, but to prepare you to return to your sport or activity feeling confident and ready to go. This is something that is often missing from rehab. I’ve worked with countless patients who either completed rehab but didn’t feel they were ready for sports again, or who never progressed beyond simple rehab exercises and were still dealing with their injury. A great way to bridge the gap between rehab and a return to your activity is to incorporate the activity into the rehab; the activity is the rehab.

When and how we do this depends on factors like the type of injury, how long it has been present, the level of pain or sensitivity, and the sport itself. For example, for a runner who just sprained their ankle, we’re going to manage their pain and swelling and work on range of motion and strength before we worry about running again. But for a runner dealing with a hamstring tendinopathy, we may still be able to incorporate some running with modified parameters into their rehab if they can tolerate it.

The reason we need to incorporate the activity into the rehab plan comes back to the S.A.I.D. principle. With continued participation in a sport, we not only develop specific adaptations to that sport, but also a level of tolerance to its demands and forces. Each sport is going to have its own unique demands on the body, and nothing can prepare you for your sport like doing the sport itself.

Looking at running again since many sports involve some form of it, each stride can result in 2-3 times a person’s body weight going through their leg at a slower pace, and up to 6-8 times body weight at faster paces. Depending on the individual, the injury and equipment available, it may be very difficult to achieve these kinds of loads with rehab and strengthening exercises alone. Simple plyometric exercises like hopping and jumping come close to reproducing these forces and can be a great introduction, but ultimately if the goal is to return to running, then at some point the body has to be exposed to running again.

It’s important not to create a false dichotomy and think that strengthening isn’t important. Strength and rehab exercises build the physical strength and power needed for the sport and support the rehab process. Sport-specific activity prepares the body for sport by reintroducing those unique demands. Likewise, it doesn’t mean we just push through pain to maintain training tolerance. A good rehab program brings the exercises and activity down to a level the person can tolerate, and builds up from there.

Incorporating the sport into the rehab can also be great from a psychological aspect. Having to stop doing an activity you enjoy can make recovery seem more unattainable as thoughts of never being able to return may creep in. Finding ways to incorporate some degree of the sport can help you feel like a return is possible and provide encouragement along the way.

Rehab shouldn’t end when the pain fades; it should end when you feel prepared, and nothing can prepare you for your sport like doing the sport itself. Modify it to what you can tolerate, and build from there. That’s how you bridge that gap physically and mentally.

Rest Is Not Lazy

Last week, I explained why rest alone is not rehab. This week, I want to address the other side of that conversation: resting isn’t being lazy. While we often feel the need to be actively doing something throughout our entire rehab, rest can be a valuable tool when used appropriately. Rest isn’t the opposite of rehab, but rather a part of it.

Last week, I explained why rest alone is not rehab. This week, I want to address the other side of that conversation: resting isn’t being lazy. While we often feel the need to be actively doing something throughout our entire rehab, rest can be a valuable tool when used appropriately. Rest isn’t the opposite of rehab, but rather a part of it.

Inflammation: Helpful Until It Isn’t

Rest is most important in the first few days following an acute injury. This phase, known as the inflammatory stage of healing, is an immune response that helps clean up the injured area and set the stage for recovery. Inflammation isn’t a bad thing — it’s necessary. However, it’s also typically the most painful phase, which serves as a reminder that the tissue is vulnerable. Ignoring this phase can lead to further injury or a larger inflammatory response, both of which can slow recovery. Gentle range-of-motion movements are often appropriate here, but rest at this stage is about respecting the healing process, not pushing through it.

Stress Builds, Rest Rebuilds

When we train in the gym, we don’t usually work the same muscle group hard on consecutive days. The time in between allows the body to recover and adapt. Rehab works the same way. Rehab exercises provide the stimulus, but the body responds and heals during rest. Without enough time to recover, even well-designed rehab exercises can become another stressor rather than a benefit.

Progress Loves Patience

Many injuries are related to doing too much, too soon, or too often without enough recovery. Overuse injuries aren’t usually caused by a single mistake, but by a gradual mismatch between training demands and recovery. Building rest into your training helps manage this. Setbacks or flare-ups aren’t failures — they’re often just load miscalculations that signal the body wasn’t fully prepared for the demands placed on it.

More Than Just the Tissue

Injury is never just a physical issue. The same biopsychosocial factors that influence injury also influence pain and recovery. Your body is constantly balancing training, work stress, sleep, nutrition, and social pressures. When rest is consistently ignored, fatigue builds and tolerance for both activity and healing drops. Strategic rest helps calm the system as a whole and not just the injured tissue.

The goal of rest isn’t to slow you down — it’s to set you up for future training. Rest is when the body repairs itself after you’ve given it a reason to adapt. Smart rehab is knowing when to push and when to pause. Rest alone isn’t rehab, but rehab without rest doesn’t work either.

Why Rest Alone Isn’t Rehab

Whenever we suffer an injury or experience pain, our first instinct is usually to rest the area. There’s the old doctor joke: “It hurts when I do this.” “Then don’t do that.” In the short term, this advice makes sense. Pain often increases with movement, so avoiding movement can help manage symptoms and reduce the fear of making things worse. Rest reduces pain, but rehab builds tolerance.

Whenever we suffer an injury or experience pain, our first instinct is usually to rest the area. There’s the old doctor joke: “It hurts when I do this.” “Then don’t do that.” In the short term, this advice makes sense. Pain often increases with movement, so avoiding movement can help manage symptoms and reduce the fear of making things worse. Rest reduces pain, but rehab builds tolerance.

The problem is that rest alone does not prepare the body to return to sport or activity. While rest can help calm pain, it doesn’t rebuild strength, tolerance, or confidence. That’s why “rest until it feels better” often leads people right back to pain or re-injury once they try to return.

This is where the idea of relative rest becomes important.

The first two to four days following an acute injury are often the most painful. This is when inflammation is active and tissues are highly sensitive. During this phase, rest is appropriate — especially from the movements or activities that clearly worsen symptoms. But even here, absolute rest isn’t ideal.

Relative rest means avoiding high-stress activities while still allowing tolerable movement. Simple actions like wiggling fingers or toes, moving the joints above and below the injury, or gentle pain-free motion can help manage swelling, maintain muscle activity, and support the healing process without overloading injured tissue. As pain begins to settle, this relative rest gradually shifts toward more direct and intentional loading.

Take a rolled ankle as an example. In the first few days, you might use crutches or a walking boot to reduce stress on the ankle and manage pain. You may also elevate it to help with swelling. This is appropriate rest, but that’s not the end of rehab. Throughout the day, you can still wiggle your toes and bend and straighten your knee. Once pain improves, ankle movement can be added in all directions, first without weight, then with gradual loading. This can progress to gentle isometrics, resisted exercises, general lower-body strengthening, and eventually running, cutting, and change-of-direction work to match the demands of your sport. At each stage, the goal isn’t just to feel better but to prepare the ankle to tolerate what’s coming next.

This is where the SAID principle comes in: Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands - or more simply, use it or lose it (read more here). When we completely rest for too long, the body adapts by losing strength, conditioning, and tolerance to load. Pain may settle, but tolerance decreases. When activity is reintroduced without rebuilding that tolerance, the body is often less prepared than before, increasing the risk of setbacks or re-injury.

Even small amounts of early loading can help maintain tolerance and limit this deconditioning. As symptoms allow, progressively increasing load is what actually restores strength, confidence, and resilience, not just in the tissue, but also in your ability to trust your body again. Rehab isn’t just about calming symptoms - it’s about making sure your body is ready to return to what you want to do.

If your rehab plan is only rest, you’re likely to stall. A smart rehab plan keeps you moving within tolerance, then gradually builds that tolerance so that when you return to sport or activity, your body is prepared.

Why the Lateral Raise Is My Go-To Exercise for Shoulder Pain

I generally don’t like using the term “best” when it comes to discussing exercises. Exercises aren’t good or bad, and there isn’t one “best” movement - everything requires context. Exercise selection should be based on the individual person’s goals, current ability, available equipment, comfort, and preferences.

I generally don’t like using the term “best” when it comes to discussing exercises. Exercises aren’t good or bad, and there isn’t one “best” movement - everything requires context. Exercise selection should be based on the individual person’s goals, current ability, available equipment, comfort, and preferences.

That said, when I’m working with people dealing with shoulder pain, I do have a go-to exercise: the lateral raise. I’m going to call it the “best” exercise for those with shoulder pain for the following reasons, some of which you might not have even considered!

Jack of All Trades

The deltoids are the eye-catching shoulder muscle, but in rehab the rotator cuff often gets most of the attention. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that provide stability to the highly mobile shoulder joint. The rotator cuff works during every shoulder movement, but certain movements load specific cuff muscles more than others. It turns out the lateral raise hits all of the rotator cuff muscles fairly equally. In cases where it is difficult determining which cuff muscle is irritated, the lateral raise can be a great first exercise to load the entire shoulder.

Easy as ABC

The lateral raise is an easy and straightforward exercise to teach, learn, and execute. Exercises like squats, deadlifts, or bench press may come with various cues and specific techniques, but for the lateral raise, you’re simply raising your straight arm to around shoulder height. This makes it an easy exercise for those who are not familiar or comfortable with resistance training. It’s also easier to remember and actually complete, instead of worrying about five different cues like you might when squatting.

You Can Go Your Own Way

The lateral raise is great because there are many ways you can modify it to suit your needs, both from a rehab and performance standpoint. If someone is having pain with this movement, turning their hands from a palms-down to a thumbs-up position, or moving their arms from straight out to the side to angled slightly forwards (T to V position) might provide relief for this exercise. If someone is getting pain at the top position, we might have them perform it while lying on their side to eliminate gravity in that position. Or we can use a resistance band that has little tension at the start if the bottom of the movement is painful.

Performance-wise, you can opt to use a cable machine (single or double-arm, standing or supine) in order to maintain tension in the bottom position. You can also achieve this by doing a single-arm lateral raise but leaning into a wall so that the weight is across your body, giving you more stretch at the start. Essentially, you have lots of different options to modify the exercise to suit your needs.

Light Weight Baby

The lateral raise is generally an exercise you do not load with very heavy a weight, due to the small muscles of the shoulder and the large moment arm when your arms are fully straight out to your side. This is great for the average person dealing with shoulder pain because you don’t need to go out and buy heavy weights. You may not even need to buy weights at all. You can get creative by using a full water bottle, a can of soup, or loading a grocery bag with household items. This makes the lateral raise an easily accessible exercise for many people to do.

I call the lateral raise my “best” shoulder exercise, not because it’s magic, but because it checks many practical boxes. It strengthens multiple muscles, it’s easy to learn, it’s adaptable when painful, and it doesn’t require much equipment. In real life, those things matter more than perfection. For many people with shoulder pain, it’s not about finding the perfect exercise - it’s finding something they can actually do consistently without flaring things up. The best exercise is the one you understand, feel confident doing, and can actually stick with.

How Dry Is Your Forest? Understanding Why Pain and Injuries Happen

When explaining why injuries occur, I often refer to the Biopsychosocial Model of pain (BPS). The BPS is a holistic model suggesting that health and well-being result from the interconnection and interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors, rather than a single cause.

When explaining why injuries occur, I often refer to the Biopsychosocial Model of pain (BPS). The BPS is a holistic model suggesting that health and well-being result from the interconnection and interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors, rather than a single cause.

But the BPS can be misunderstood by both patients and therapists. BPS doesn’t explain injury, but rather just considers multiple factors as opposed to specific causes. Some assume everything has to be perfectly balanced to remain injury-free. There are two problems with this: first, it’s impossible to have every aspect of life going perfectly at once, and second, it treats any single “off” factor as the cause of injury. One common argument against BPS is the incorrect interpretation that “it’s all in your head.” While this argument only factors in the psychological component, it’s generally meant that the physical factors, like movement, technique, biomechanics, and load, are ignored.

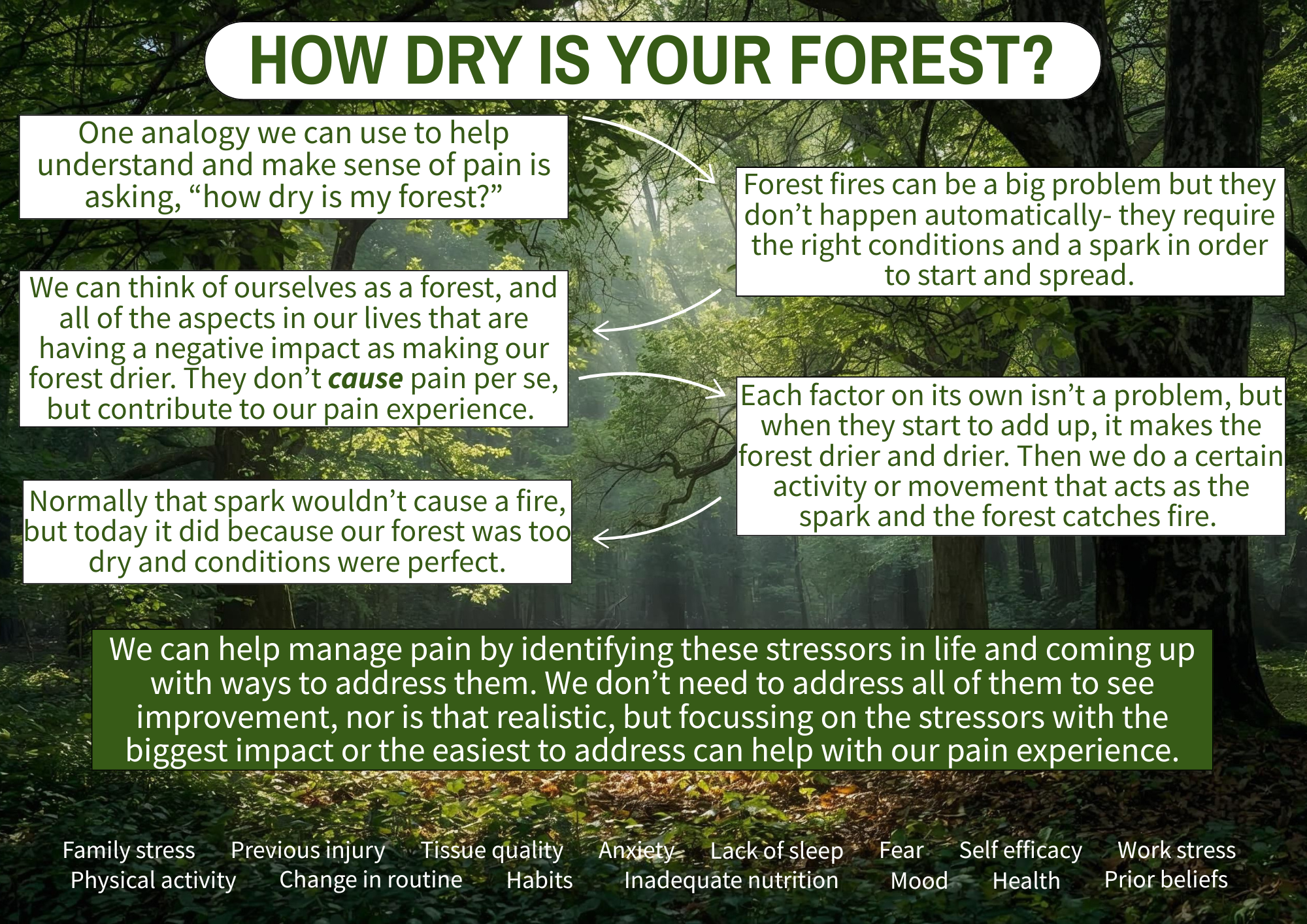

One analogy I really like that helps better explain BPS is asking yourself, “how dry is your forest?” This analogy comes from Ben Cormack, who suggests that many factors can make the forest dry, which then only requires a small spark to trigger a fire (i.e. pain). Greg Lehman has a similar analogy, asking how healthy is your ecosystem?

Think of yourself when you’re completely healthy as a nice, lush, green forest. Forest fires (pain and injury) are a problem, but they don’t occur automatically. Rather, they require the right conditions to start and spread. The factors under the three realms of the BPS can all individually make our forest drier; the degree to which they impact your forest will vary.

Biological factors include training volume, previous injury, nutrition, and sleep. Psychological factors include self-efficacy, confidence, mood, and anxiety. Social factors include work and family stress, habits, routines, and social support.

None of these factors cause pain, and each on its own is not a problem, but when they add up, they make our forest drier and drier. A lush forest would need a very big spark in order to start a fire, but a dry forest would only need a small spark.

This may explain the confusion people have when they feel they are doing everything right but still suffer an injury. “I only ran an extra 2km this week, and now my knee hurts.” In a lush forest, that 2km spark would not have been enough to start a fire, but in a dry forest, it was the perfect condition. Being stressed at work and not sleeping as well didn’t cause the pain, but they contributed to that 2km jump in training volume being more than what your body could tolerate.

The good news is that we don’t need to tackle all of the factors in order to see improvements in pain (nor is that realistic). Often, focusing on the stressors with the biggest impact or the easiest to change is enough. Taking the approach of “how can I be healthier” can also help as it will usually tackle several factors at once. But remember, these factors did not cause your injury but rather predisposed you or made an injury more likely. Sometimes the best course is to just acknowledge what has made our forest dry and to do our best to avoid a spark when our forest is dry.

The goal isn’t to find a single cause of pain. The goal is to understand what has dried out your forest, reduce a few key risk factors, and gradually rebuild capacity again.

What Managing My Own Knee Pain Has Reinforced About Rehab

Since I started running again almost a year ago, I’ve dealt with a few aches and pains. This most recent episode highlights a familiar situation for runners: staying active while still being smart with training.

Since I started running again almost a year ago, I’ve dealt with a few aches and pains. This most recent episode highlights a familiar situation for runners: staying active while still being smart with training.

Quick Summary

I had been consistent with my running into November, training four times a week with long, easy, and speed runs, while also lifting weights twice a week. During my first interval session of my program, I was exhausted early on and couldn’t complete the session. The following week, I noticed stiffness in my right knee when standing up from squatting while doing laundry, but I didn’t think much of it.

Over the next few weeks, travel and sickness disrupted my consistency. I still managed some runs, including an LSD PR of 13km, but during this run I noticed some lateral right knee pain. However, this didn’t affect my run and did not linger. Once I was back on track, I reorganized my plan to repeat a week, which led me to my 10km tempo run. At 4km I felt the same pain on my lateral knee and suddenly at 8km I was limping.

Even walking around the house, my knee was still hurting, but I still got outside for walks, trying to avoid hills as they were painful. About a week later, I attempted a run-walk to see if I could tolerate shorter runs interspersed with walking, but this was still immediately painful. Based on this, I decided to stop running until the pain improved. After doing some exercises and allowing the time, I ran the first kilometre of a 2km walk-run pain-free.

What the Heck is Going On?

Based on the location of the pain and how it worsened with bending and straightening my knee with running and walking, I would describe this as iliotibial band (ITB) related pain, a common running injury. The ITB is a thick, fibrous band of tissue formed by the gluteal muscles and inserting just below the knee. Its function is to increase the leverage of the gluteal muscles.

I don’t like calling this an “injury” as that implies damage to my knee, and there was no clear mechanism or event to suggest a tear. I feel it is more accurate to describe it as training errors leading to an overload and sensitization of my ITB causing pain.

Several factors in my training and life have led to this overload in my knee:

I didn’t sleep well or fuel myself enough prior to that first interval session, and I was stressed about an upcoming meeting later that day; all not ideal to then be going for an intense run.

Taking seven and 11 days off due to travel and sickness made my running volume inconsistent. While I hoped my capacity wouldn’t have dropped that much, running while sick was not ideal.

The strength training portion of my program also lacked consistency during this entire time. I didn’t necessarily get weaker, but it was still a break in training.

I jumped back in too quickly with a 10km tempo run despite slowing my pace. Although the distance was the same, it had been four weeks since my last tempo run.

What I am Doing to Manage

This became a red light situation for me, not because I was worried about damaging my knee, but because I knew based on the limping and lingering pain that running would only prolong this. I tried to compromise by doing the run-walk, but the immediate pain told me I needed a break until I could walk a significant time/distance (including hills) pain-free.

I chose to continue walking to stay active, trying to avoid hills and starting with slower and shorter walks. I also refocused on my strengthening, trying to find exercises that would be helpful. I started with some lateral hip and gluteal strengthening, which initially provided relief, but then focused on my quadriceps strength inspired by the pain with walking downhill. I chose Bulgarian split squats as my main exercise as I could load in a single-leg and bent knee position. My knee improved once I significantly increased the weight after the initial painful phase. I also added some hopping to re-accustom myself to the single leg loading of running.

Just last weekend, I went for a walk-run, opting to start with walking to get warmed up and stuck to a distance, even if it went well. The first kilometre of running was pain-free, but the second had some pain, though manageable. I plan to continue running as the pain is down to a yellow light, ensuring I continue to improve before restarting continuous running.

Even as an athletic therapist, I am still active myself. I started running again with walk-runs last January after 14 years, only to end up back at them and having to build myself back up. Like many setbacks though, the silver lining is the opportunity to reflect, evaluate your program, make changes, and learn from your mistakes. I now know for the future that even taking just a week or two off requires some adjustments to my running volume. I don’t feel this current pain was caused by running mechanics or lack of strength. While these factors are often cited as causes, they ignore all of the other factors that lower capacity and/or increase load. I don’t feel any single factor was the cause— they all contributed to create the ideal conditions for ITB-related pain.

To Summarize

My ITB-related knee pain developed due to various factors, forming the perfect storm.

This is not an injury, but pain due to overload and training errors.

Several internal factors and a jump in interval volume likely triggered the knee sensitivity.

I had gaps in my running and strengthening consistency, further lowering my capacity.

I had two load spikes that were more than I could tolerate, resulting in the ITB pain.

I remained active with walking despite some pain, and added strengthening exercises specific for my knee.

I will continue to progress my walk-runs to continuous running, using pain both during and after to guide my progress.

Pain rarely comes down to one thing, and rehab rarely follows a straight line. What matters more than finding the “cause” is having a way to make decisions as symptoms change. This is the same framework I use with clients — not because it guarantees a perfect outcome, but because it gives us a clear way to adapt, stay active where possible, and keep moving forward even when things don’t go to plan.

Is All Stress Bad?

“Stress” is used in the strength and conditioning, training, and rehab world with a negative connotation. We hear people say, “don’t do the knee extension machine because it stresses your knees” or “deadlifts put stress on your low back.” While said with good intentions, there is a lot of context missing in these statements. Rather than viewing stress as only bad, we need to look back at the SAID principle to see how stress can be a good thing.

When we hear the word “stress”, we tend to think of it as being a negative thing. Chronic stress can certainly have physical, emotional, and behavioural symptoms and sequelae affecting your health. But stress is the body’s natural response to pressure or demands, and in the short term, it can be extremely motivating, such as finishing a project before a deadline or running away from a dangerous situation.

But “stress” is also used in the strength and conditioning, training, and rehab world with a negative connotation. We hear people say, “don’t do the knee extension machine because it stresses your knees” or “deadlifts put stress on your low back.” While said with good intentions, there is a lot of context missing in these statements. Rather than viewing stress as only bad, we need to look back at the SAID principle to see how stress can be a good thing.

The stress we’re usually referring to in the rehab world is the physical demands we place on our bodies through physical activity. In material science and physics, the mathematical formula for stress is: stress = force / surface area. This formula explains why it is dangerous to step on a single nail but safe to lay on a bed of nails. When stepping on a nail, you have your entire body weight (the force) coming down through your foot onto the pinpoint (surface area) of a nail. But when you lay on a bed of nails, your body weight is displaced over a larger surface area, despite still being sharp nails.

This is usually the context that people use when it comes to stress and exercise. In the above comment about knee extensions stressing the knee, the implied warning is that weight, positioning, and movement from the knee extension machine applied more force over the small knee cap. What is usually offered as a safer alternative is squats, as the movement allows for more muscles and joints to be used to lessen the stress on the knee via a larger surface area.

While mathematically this may be true, it is important to remember that the human body is not a machine and is capable of adaptation. Just like you shouldn’t start your first day of running by doing a marathon, you should be selecting an appropriate weight for the knee extension machine. With time and consistency, you should be able to progress your weight because your body adapts and gets stronger, even if it is more “stressful” than other leg exercises. As well, the human body is highly individualistic. While one person may find the knee extension machine irritating for their knees, someone else may find this perfectly fine and a great quadriceps-isolation exercise. Differences in anatomy, training history, previous injuries, and beliefs are some examples of why an exercise would vary between people.

We can also refer to stress in a more general sense when we think of our training program and physical activities as a whole, and our ability to recover from them. This is where semantics may muddle things, as sometimes stress, load, and volume are used interchangeably when referring to the total amount of physical activity someone is doing. But in reality, when we do physical activity, we are increasing the demands on our cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems, thereby “stressing” them. But this stress is needed, as it is the main driving force for adaptation and improving these systems. If we don’t stress our bodies enough, we don’t see improvements in our function, and we may even regress. If we over-stress our bodies with excessive activity, we’re not allowing for the recovery needed to cause improvements, and we may even be setting ourselves up for injury and burnout.

When we talk about stress in rehab, there needs to be context behind it. Stress is just a number, or rather just the representation of force over surface area - it means nothing without context and is inherently neither good nor bad. Stress, both the colloquial and mathematical meaning, in rehab is necessary for a full recovery. An injured muscle, tendon, ligament, or bone must be loaded and stressed in order to induce physiological adaptations leading to the healing of the tissue with greater strength capabilities if one hopes to return to physical activity pain-free. The timing of this stress and the amount of stress are key though in a rehab program— stressing a tissue too early or too much can certainly cause setbacks, but we also want to make sure we’re not delaying or under-stressing the tissue as this will not set us up for success.

Stress is necessary, but whether it helps or harms depends on how much you can tolerate at the time. Rehab then isn’t about avoiding stress, but about applying the right amount at the right time, based on what the person can tolerate.

Understanding the S.A.I.D. Principle in Rehab

An important concept I apply to my rehab, borrowed from the strength and conditioning world, is the SAID principle, which stands for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. What this means is that how and what we train determines how our body adapts. Or even simpler, we get better at what we do.

An important concept I apply to my rehab, borrowed from the strength and conditioning world, is the SAID principle, which stands for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. What this means is that how and what we train determines how our body adapts. Or even simpler, we get better at what we do.

For example, if a runner mainly trains with short sprints and drills to build maximum speed, they’ll become a better sprinter, but that won’t prepare them to complete a marathon. On the flip side, a runner focused on long distance endurance will do well in a marathon but won’t be the fastest sprinter. Both may include some elements of each other’s training, but their bodies adapt specifically to the type of work they do. That is the SAID principle in action- our body adapts to the demands we place on it.

In rehab, applying the SAID principle helps the body prepare for the stresses and demands of sport or activity. This becomes especially important in the later stages of recovery as we bridge the gap between rehab and competition.

Using our runner example again, after a hamstring strain, we want to load the hamstring early, but appropriately. This might start with a simple exercise like digging the heel into the floor and sliding it toward the hips at a tolerable intensity. From there, we’d progress to a weighted hamstring curl and gradually increase load. Because they’re a runner, we’d also include other lower-body exercises like leg extensions, hip abductions, and calf raises.

As their strength improves, we can progress to multi-joint exercises like squats, deadlifts, or RDLs. Squats are great because they don’t heavily load the hamstrings but still strengthen the quads and glutes. Deadlifts and RDLs may also be well tolerated since they involve multiple muscles and place more emphasis at the hip — depending on the location of the strain.

Next, we’d add single-leg work, followed by plyometric or power exercises like hopping, skipping, and bounding. These more closely resemble the single-leg loading and push-off nature of running.

We’d also begin to reintroduce running itself — starting with slower speeds and shorter durations, then building from there. Returning to running is a graded exposure to the specific demands of running. It’s not about sport mimicry; it’s about directly applying the SAID principle by progressively exposing the hamstring to the real forces it will face.

Sometimes, though, the SAID principle is taken too far. We start believing every exercise must match or mimic the sport exactly — using single-limb movements, unstable surfaces, or weighted sport-specific motions. These have their place, but it’s important to recognize the different roles of strength training and sport practice.

The goal of strength and conditioning is to build muscular strength and power — to help your body generate more force.

The goal of sport and skills training is to improve coordination, timing, and technique within the sport itself.

Working out in the gym won’t automatically make you a better soccer player, just like playing soccer won’t make you jacked. Both are vital — but they need to be trained separately. If the goal is to build strength that transfers into sport, we need to maximize load on the muscles. Single-leg squats and lunges are useful, but they can’t be loaded as heavily as a barbell squat. Both can be included in a training week or within a periodized plan — but our gym sessions don’t need to look like our practice sessions.

Of course, the SAID principle can also be underused. Sometimes rehab consists only of a resistance band and a few easy exercises, with minimal load or challenge. In these cases, there’s not enough demand on the muscle to drive adaptation.

There’s always nuance and context to every rehab plan. But overall, we want to apply the SAID principle by ensuring our exercises appropriately load and challenge the injured area, progress in complexity and demand, and build capacity for return to sport. What we don’t need to do is make every exercise look like the sport itself — because we’ll reintroduce those sport movements separately, starting at low intensity and building from there.

In summary, the SAID principle reminds us that our body adapts to exactly what we demand of it. In rehab, that means loading the injured area appropriately and progressing toward the real demand of your sport, without trying to turn every exercise into a copy of the sport itself.

A Traffic Light Guide To Exercising With Pain

One of the harder parts of the rehab process from the practitioner side, and what makes rehab sometimes more of an art than science, is knowing when we accept pain during the rehab process.

One of the harder parts of the rehab process from the practitioner side, and what makes rehab sometimes more of an art than science, is knowing when we accept pain during the rehab process. While we do have general guidelines, such as saving eccentrics for the later stages, or not progressing weights too quickly, we are working with human beings who are dealing with the experience of pain. The problem though is, pain is not always a reliable experience. The challenge then becomes when do we trust pain and when do we not? Or maybe a more relevant question is, when is it okay to work through pain? We’ve all experienced the “no pain, no gain” mentality in some form, but this may not always be the best approach depending on your injury.

The short answer is yes, it is okay to work through some pain, but with a bit of common sense. Of course context matters, so we’ll break it down a bit further, but knowing when to push and when to tweak or even hit pause can have a big impact on your recovery.

This is an important concept to address because pain is a complex, individual and multifactorial experience, meaning that everyone experiences it differently and there can be many factors influencing your pain. Pain is also contextual— we (patients and practitioners) seem to accept pain when we’re providing hands-on treatment. I lost track of the number of times someone would ask for more pressure during a massage despite them wincing in pain, or who thought that more would mean a faster recovery. But then when it comes to exercise, we tend to quickly abandon an exercise if the patient experiences any pain with it. So why do we accept pain in some cases, but not others (rhetorical question for the purpose of this blog).

Just know that pain doesn’t always mean damage during the rehab process. The tissue can still be sensitive to loading without resulting in further damage or reinjury. When it comes to pain that develops through overuse or pain that lasts beyond the typical healing time, that’s when pain can be a bit more unreliable, and is still more about sensitivity than damage. Staying active and mobile can help with recovery, provided it is within reason. Being unsure of what is safe or not can certainly cause a dilemma with your recovery - if you back off you might be under-loading yourself, but if you keep going you might be overloading yourself. Neither of these are ideal. But there is a simple analogy you can use to help better gauge your pain and add some clarity to the decision to work through pain during your rehab— the traffic light.

Green Means Go!

In these cases, the pain is mild— I usually consider this to be a self-rated 4/10 or less on the pain scale. This pain generally settles down fairly soon after exercise, or at least within 24 hours, and during the exercise you’re still moving well and feeling confident. This is a good space to work in. The pain is there, but it is not modifying how you perform. You might feel a twinge or ache, but you’re not doing any harm, and your body can handle this. This doesn’t mean that we’re in the clear to go crazy, but it does give an indication that we’re in a good spot with the loading. You should still continue to monitor the pain though, because that leads into…

Yellow Means Caution (and Adjust)

This is when the pain increases to a 5/10 or 6/10 on the pain scale, and usually the pain lingers longer than 24 hours before subsiding. Movements might feel a little forced or you might feel guarded, hesitant, deliberate, or cautious during activity. We may not be causing physical damage yet, but we’re certainly starting to push the limits of what the injured tissue can tolerate, and we need to adjust accordingly. The good news is we can still continue some form of exercise, and there are many ways you can adjust to get back into a green light— changing the movement or reducing the weight are just a couple of examples.

Red Means Stop (For Now)

I don’t like having patients stop their exercises, and there are always some unrelated activities they can do to remain active, but sometimes stopping an aggravating exercise is needed. These are cases when the pain is a 7/10 or more; the pain sticks around at that level for longer, or even worsens, and you’re uncomfortable or hesitant to move. This is your cue to rest or scale back to simpler movements that calm the area down, rather than push through and hope for the best because we are at a higher risk of injury. It may seem like we’re losing progress, when really it is just being smart—short-term sacrifice for long-term gain.

It’s okay to feel some pain during the rehab process— tolerable pain doesn’t mean something is injured further. In fact, some studies show it leads to better outcomes than completely avoiding pain (maybe the point when you feel pain is the lower end of the stimulus threshold to cause adaptation, so by avoiding pain you’re not providing adequate stimulation). There’s no need to panic, but it is still worth paying attention to to see how it changes. Maybe it is just a one-off thing because you didn’t sleep very well the night before or maybe it’s a sign that you are not tolerating the exercise well and an adjustment is needed.

Staying active helps the healing process, as long as we are respecting that process and respecting where your body is at.