The Activity is the Rehab

The purpose of a rehab plan shouldn't be just to get you out of pain and heal the injured area, but to prepare you to return to your sport or activity feeling confident and ready to go. This is something that is often missing from rehab.

The purpose of a rehab plan shouldn't be just to get you out of pain and heal the injured area, but to prepare you to return to your sport or activity feeling confident and ready to go. This is something that is often missing from rehab. I’ve worked with countless patients who either completed rehab but didn’t feel they were ready for sports again, or who never progressed beyond simple rehab exercises and were still dealing with their injury. A great way to bridge the gap between rehab and a return to your activity is to incorporate the activity into the rehab; the activity is the rehab.

When and how we do this depends on factors like the type of injury, how long it has been present, the level of pain or sensitivity, and the sport itself. For example, for a runner who just sprained their ankle, we’re going to manage their pain and swelling and work on range of motion and strength before we worry about running again. But for a runner dealing with a hamstring tendinopathy, we may still be able to incorporate some running with modified parameters into their rehab if they can tolerate it.

The reason we need to incorporate the activity into the rehab plan comes back to the S.A.I.D. principle. With continued participation in a sport, we not only develop specific adaptations to that sport, but also a level of tolerance to its demands and forces. Each sport is going to have its own unique demands on the body, and nothing can prepare you for your sport like doing the sport itself.

Looking at running again since many sports involve some form of it, each stride can result in 2-3 times a person’s body weight going through their leg at a slower pace, and up to 6-8 times body weight at faster paces. Depending on the individual, the injury and equipment available, it may be very difficult to achieve these kinds of loads with rehab and strengthening exercises alone. Simple plyometric exercises like hopping and jumping come close to reproducing these forces and can be a great introduction, but ultimately if the goal is to return to running, then at some point the body has to be exposed to running again.

It’s important not to create a false dichotomy and think that strengthening isn’t important. Strength and rehab exercises build the physical strength and power needed for the sport and support the rehab process. Sport-specific activity prepares the body for sport by reintroducing those unique demands. Likewise, it doesn’t mean we just push through pain to maintain training tolerance. A good rehab program brings the exercises and activity down to a level the person can tolerate, and builds up from there.

Incorporating the sport into the rehab can also be great from a psychological aspect. Having to stop doing an activity you enjoy can make recovery seem more unattainable as thoughts of never being able to return may creep in. Finding ways to incorporate some degree of the sport can help you feel like a return is possible and provide encouragement along the way.

Rehab shouldn’t end when the pain fades; it should end when you feel prepared, and nothing can prepare you for your sport like doing the sport itself. Modify it to what you can tolerate, and build from there. That’s how you bridge that gap physically and mentally.

Rest Is Not Lazy

Last week, I explained why rest alone is not rehab. This week, I want to address the other side of that conversation: resting isn’t being lazy. While we often feel the need to be actively doing something throughout our entire rehab, rest can be a valuable tool when used appropriately. Rest isn’t the opposite of rehab, but rather a part of it.

Last week, I explained why rest alone is not rehab. This week, I want to address the other side of that conversation: resting isn’t being lazy. While we often feel the need to be actively doing something throughout our entire rehab, rest can be a valuable tool when used appropriately. Rest isn’t the opposite of rehab, but rather a part of it.

Inflammation: Helpful Until It Isn’t

Rest is most important in the first few days following an acute injury. This phase, known as the inflammatory stage of healing, is an immune response that helps clean up the injured area and set the stage for recovery. Inflammation isn’t a bad thing — it’s necessary. However, it’s also typically the most painful phase, which serves as a reminder that the tissue is vulnerable. Ignoring this phase can lead to further injury or a larger inflammatory response, both of which can slow recovery. Gentle range-of-motion movements are often appropriate here, but rest at this stage is about respecting the healing process, not pushing through it.

Stress Builds, Rest Rebuilds

When we train in the gym, we don’t usually work the same muscle group hard on consecutive days. The time in between allows the body to recover and adapt. Rehab works the same way. Rehab exercises provide the stimulus, but the body responds and heals during rest. Without enough time to recover, even well-designed rehab exercises can become another stressor rather than a benefit.

Progress Loves Patience

Many injuries are related to doing too much, too soon, or too often without enough recovery. Overuse injuries aren’t usually caused by a single mistake, but by a gradual mismatch between training demands and recovery. Building rest into your training helps manage this. Setbacks or flare-ups aren’t failures — they’re often just load miscalculations that signal the body wasn’t fully prepared for the demands placed on it.

More Than Just the Tissue

Injury is never just a physical issue. The same biopsychosocial factors that influence injury also influence pain and recovery. Your body is constantly balancing training, work stress, sleep, nutrition, and social pressures. When rest is consistently ignored, fatigue builds and tolerance for both activity and healing drops. Strategic rest helps calm the system as a whole and not just the injured tissue.

The goal of rest isn’t to slow you down — it’s to set you up for future training. Rest is when the body repairs itself after you’ve given it a reason to adapt. Smart rehab is knowing when to push and when to pause. Rest alone isn’t rehab, but rehab without rest doesn’t work either.

Why Rest Alone Isn’t Rehab

Whenever we suffer an injury or experience pain, our first instinct is usually to rest the area. There’s the old doctor joke: “It hurts when I do this.” “Then don’t do that.” In the short term, this advice makes sense. Pain often increases with movement, so avoiding movement can help manage symptoms and reduce the fear of making things worse. Rest reduces pain, but rehab builds tolerance.

Whenever we suffer an injury or experience pain, our first instinct is usually to rest the area. There’s the old doctor joke: “It hurts when I do this.” “Then don’t do that.” In the short term, this advice makes sense. Pain often increases with movement, so avoiding movement can help manage symptoms and reduce the fear of making things worse. Rest reduces pain, but rehab builds tolerance.

The problem is that rest alone does not prepare the body to return to sport or activity. While rest can help calm pain, it doesn’t rebuild strength, tolerance, or confidence. That’s why “rest until it feels better” often leads people right back to pain or re-injury once they try to return.

This is where the idea of relative rest becomes important.

The first two to four days following an acute injury are often the most painful. This is when inflammation is active and tissues are highly sensitive. During this phase, rest is appropriate — especially from the movements or activities that clearly worsen symptoms. But even here, absolute rest isn’t ideal.

Relative rest means avoiding high-stress activities while still allowing tolerable movement. Simple actions like wiggling fingers or toes, moving the joints above and below the injury, or gentle pain-free motion can help manage swelling, maintain muscle activity, and support the healing process without overloading injured tissue. As pain begins to settle, this relative rest gradually shifts toward more direct and intentional loading.

Take a rolled ankle as an example. In the first few days, you might use crutches or a walking boot to reduce stress on the ankle and manage pain. You may also elevate it to help with swelling. This is appropriate rest, but that’s not the end of rehab. Throughout the day, you can still wiggle your toes and bend and straighten your knee. Once pain improves, ankle movement can be added in all directions, first without weight, then with gradual loading. This can progress to gentle isometrics, resisted exercises, general lower-body strengthening, and eventually running, cutting, and change-of-direction work to match the demands of your sport. At each stage, the goal isn’t just to feel better but to prepare the ankle to tolerate what’s coming next.

This is where the SAID principle comes in: Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands - or more simply, use it or lose it (read more here). When we completely rest for too long, the body adapts by losing strength, conditioning, and tolerance to load. Pain may settle, but tolerance decreases. When activity is reintroduced without rebuilding that tolerance, the body is often less prepared than before, increasing the risk of setbacks or re-injury.

Even small amounts of early loading can help maintain tolerance and limit this deconditioning. As symptoms allow, progressively increasing load is what actually restores strength, confidence, and resilience, not just in the tissue, but also in your ability to trust your body again. Rehab isn’t just about calming symptoms - it’s about making sure your body is ready to return to what you want to do.

If your rehab plan is only rest, you’re likely to stall. A smart rehab plan keeps you moving within tolerance, then gradually builds that tolerance so that when you return to sport or activity, your body is prepared.

Why the Lateral Raise Is My Go-To Exercise for Shoulder Pain

I generally don’t like using the term “best” when it comes to discussing exercises. Exercises aren’t good or bad, and there isn’t one “best” movement - everything requires context. Exercise selection should be based on the individual person’s goals, current ability, available equipment, comfort, and preferences.

I generally don’t like using the term “best” when it comes to discussing exercises. Exercises aren’t good or bad, and there isn’t one “best” movement - everything requires context. Exercise selection should be based on the individual person’s goals, current ability, available equipment, comfort, and preferences.

That said, when I’m working with people dealing with shoulder pain, I do have a go-to exercise: the lateral raise. I’m going to call it the “best” exercise for those with shoulder pain for the following reasons, some of which you might not have even considered!

Jack of All Trades

The deltoids are the eye-catching shoulder muscle, but in rehab the rotator cuff often gets most of the attention. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that provide stability to the highly mobile shoulder joint. The rotator cuff works during every shoulder movement, but certain movements load specific cuff muscles more than others. It turns out the lateral raise hits all of the rotator cuff muscles fairly equally. In cases where it is difficult determining which cuff muscle is irritated, the lateral raise can be a great first exercise to load the entire shoulder.

Easy as ABC

The lateral raise is an easy and straightforward exercise to teach, learn, and execute. Exercises like squats, deadlifts, or bench press may come with various cues and specific techniques, but for the lateral raise, you’re simply raising your straight arm to around shoulder height. This makes it an easy exercise for those who are not familiar or comfortable with resistance training. It’s also easier to remember and actually complete, instead of worrying about five different cues like you might when squatting.

You Can Go Your Own Way

The lateral raise is great because there are many ways you can modify it to suit your needs, both from a rehab and performance standpoint. If someone is having pain with this movement, turning their hands from a palms-down to a thumbs-up position, or moving their arms from straight out to the side to angled slightly forwards (T to V position) might provide relief for this exercise. If someone is getting pain at the top position, we might have them perform it while lying on their side to eliminate gravity in that position. Or we can use a resistance band that has little tension at the start if the bottom of the movement is painful.

Performance-wise, you can opt to use a cable machine (single or double-arm, standing or supine) in order to maintain tension in the bottom position. You can also achieve this by doing a single-arm lateral raise but leaning into a wall so that the weight is across your body, giving you more stretch at the start. Essentially, you have lots of different options to modify the exercise to suit your needs.

Light Weight Baby

The lateral raise is generally an exercise you do not load with very heavy a weight, due to the small muscles of the shoulder and the large moment arm when your arms are fully straight out to your side. This is great for the average person dealing with shoulder pain because you don’t need to go out and buy heavy weights. You may not even need to buy weights at all. You can get creative by using a full water bottle, a can of soup, or loading a grocery bag with household items. This makes the lateral raise an easily accessible exercise for many people to do.

I call the lateral raise my “best” shoulder exercise, not because it’s magic, but because it checks many practical boxes. It strengthens multiple muscles, it’s easy to learn, it’s adaptable when painful, and it doesn’t require much equipment. In real life, those things matter more than perfection. For many people with shoulder pain, it’s not about finding the perfect exercise - it’s finding something they can actually do consistently without flaring things up. The best exercise is the one you understand, feel confident doing, and can actually stick with.

Is All Stress Bad?

“Stress” is used in the strength and conditioning, training, and rehab world with a negative connotation. We hear people say, “don’t do the knee extension machine because it stresses your knees” or “deadlifts put stress on your low back.” While said with good intentions, there is a lot of context missing in these statements. Rather than viewing stress as only bad, we need to look back at the SAID principle to see how stress can be a good thing.

When we hear the word “stress”, we tend to think of it as being a negative thing. Chronic stress can certainly have physical, emotional, and behavioural symptoms and sequelae affecting your health. But stress is the body’s natural response to pressure or demands, and in the short term, it can be extremely motivating, such as finishing a project before a deadline or running away from a dangerous situation.

But “stress” is also used in the strength and conditioning, training, and rehab world with a negative connotation. We hear people say, “don’t do the knee extension machine because it stresses your knees” or “deadlifts put stress on your low back.” While said with good intentions, there is a lot of context missing in these statements. Rather than viewing stress as only bad, we need to look back at the SAID principle to see how stress can be a good thing.

The stress we’re usually referring to in the rehab world is the physical demands we place on our bodies through physical activity. In material science and physics, the mathematical formula for stress is: stress = force / surface area. This formula explains why it is dangerous to step on a single nail but safe to lay on a bed of nails. When stepping on a nail, you have your entire body weight (the force) coming down through your foot onto the pinpoint (surface area) of a nail. But when you lay on a bed of nails, your body weight is displaced over a larger surface area, despite still being sharp nails.

This is usually the context that people use when it comes to stress and exercise. In the above comment about knee extensions stressing the knee, the implied warning is that weight, positioning, and movement from the knee extension machine applied more force over the small knee cap. What is usually offered as a safer alternative is squats, as the movement allows for more muscles and joints to be used to lessen the stress on the knee via a larger surface area.

While mathematically this may be true, it is important to remember that the human body is not a machine and is capable of adaptation. Just like you shouldn’t start your first day of running by doing a marathon, you should be selecting an appropriate weight for the knee extension machine. With time and consistency, you should be able to progress your weight because your body adapts and gets stronger, even if it is more “stressful” than other leg exercises. As well, the human body is highly individualistic. While one person may find the knee extension machine irritating for their knees, someone else may find this perfectly fine and a great quadriceps-isolation exercise. Differences in anatomy, training history, previous injuries, and beliefs are some examples of why an exercise would vary between people.

We can also refer to stress in a more general sense when we think of our training program and physical activities as a whole, and our ability to recover from them. This is where semantics may muddle things, as sometimes stress, load, and volume are used interchangeably when referring to the total amount of physical activity someone is doing. But in reality, when we do physical activity, we are increasing the demands on our cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems, thereby “stressing” them. But this stress is needed, as it is the main driving force for adaptation and improving these systems. If we don’t stress our bodies enough, we don’t see improvements in our function, and we may even regress. If we over-stress our bodies with excessive activity, we’re not allowing for the recovery needed to cause improvements, and we may even be setting ourselves up for injury and burnout.

When we talk about stress in rehab, there needs to be context behind it. Stress is just a number, or rather just the representation of force over surface area - it means nothing without context and is inherently neither good nor bad. Stress, both the colloquial and mathematical meaning, in rehab is necessary for a full recovery. An injured muscle, tendon, ligament, or bone must be loaded and stressed in order to induce physiological adaptations leading to the healing of the tissue with greater strength capabilities if one hopes to return to physical activity pain-free. The timing of this stress and the amount of stress are key though in a rehab program— stressing a tissue too early or too much can certainly cause setbacks, but we also want to make sure we’re not delaying or under-stressing the tissue as this will not set us up for success.

Stress is necessary, but whether it helps or harms depends on how much you can tolerate at the time. Rehab then isn’t about avoiding stress, but about applying the right amount at the right time, based on what the person can tolerate.

Understanding the S.A.I.D. Principle in Rehab

An important concept I apply to my rehab, borrowed from the strength and conditioning world, is the SAID principle, which stands for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. What this means is that how and what we train determines how our body adapts. Or even simpler, we get better at what we do.

An important concept I apply to my rehab, borrowed from the strength and conditioning world, is the SAID principle, which stands for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. What this means is that how and what we train determines how our body adapts. Or even simpler, we get better at what we do.

For example, if a runner mainly trains with short sprints and drills to build maximum speed, they’ll become a better sprinter, but that won’t prepare them to complete a marathon. On the flip side, a runner focused on long distance endurance will do well in a marathon but won’t be the fastest sprinter. Both may include some elements of each other’s training, but their bodies adapt specifically to the type of work they do. That is the SAID principle in action- our body adapts to the demands we place on it.

In rehab, applying the SAID principle helps the body prepare for the stresses and demands of sport or activity. This becomes especially important in the later stages of recovery as we bridge the gap between rehab and competition.

Using our runner example again, after a hamstring strain, we want to load the hamstring early, but appropriately. This might start with a simple exercise like digging the heel into the floor and sliding it toward the hips at a tolerable intensity. From there, we’d progress to a weighted hamstring curl and gradually increase load. Because they’re a runner, we’d also include other lower-body exercises like leg extensions, hip abductions, and calf raises.

As their strength improves, we can progress to multi-joint exercises like squats, deadlifts, or RDLs. Squats are great because they don’t heavily load the hamstrings but still strengthen the quads and glutes. Deadlifts and RDLs may also be well tolerated since they involve multiple muscles and place more emphasis at the hip — depending on the location of the strain.

Next, we’d add single-leg work, followed by plyometric or power exercises like hopping, skipping, and bounding. These more closely resemble the single-leg loading and push-off nature of running.

We’d also begin to reintroduce running itself — starting with slower speeds and shorter durations, then building from there. Returning to running is a graded exposure to the specific demands of running. It’s not about sport mimicry; it’s about directly applying the SAID principle by progressively exposing the hamstring to the real forces it will face.

Sometimes, though, the SAID principle is taken too far. We start believing every exercise must match or mimic the sport exactly — using single-limb movements, unstable surfaces, or weighted sport-specific motions. These have their place, but it’s important to recognize the different roles of strength training and sport practice.

The goal of strength and conditioning is to build muscular strength and power — to help your body generate more force.

The goal of sport and skills training is to improve coordination, timing, and technique within the sport itself.

Working out in the gym won’t automatically make you a better soccer player, just like playing soccer won’t make you jacked. Both are vital — but they need to be trained separately. If the goal is to build strength that transfers into sport, we need to maximize load on the muscles. Single-leg squats and lunges are useful, but they can’t be loaded as heavily as a barbell squat. Both can be included in a training week or within a periodized plan — but our gym sessions don’t need to look like our practice sessions.

Of course, the SAID principle can also be underused. Sometimes rehab consists only of a resistance band and a few easy exercises, with minimal load or challenge. In these cases, there’s not enough demand on the muscle to drive adaptation.

There’s always nuance and context to every rehab plan. But overall, we want to apply the SAID principle by ensuring our exercises appropriately load and challenge the injured area, progress in complexity and demand, and build capacity for return to sport. What we don’t need to do is make every exercise look like the sport itself — because we’ll reintroduce those sport movements separately, starting at low intensity and building from there.

In summary, the SAID principle reminds us that our body adapts to exactly what we demand of it. In rehab, that means loading the injured area appropriately and progressing toward the real demand of your sport, without trying to turn every exercise into a copy of the sport itself.

A Traffic Light Guide To Exercising With Pain

One of the harder parts of the rehab process from the practitioner side, and what makes rehab sometimes more of an art than science, is knowing when we accept pain during the rehab process.

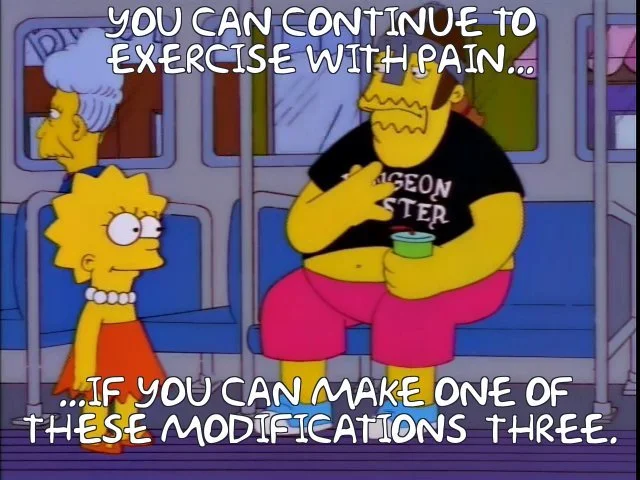

One of the harder parts of the rehab process from the practitioner side, and what makes rehab sometimes more of an art than science, is knowing when we accept pain during the rehab process. While we do have general guidelines, such as saving eccentrics for the later stages, or not progressing weights too quickly, we are working with human beings who are dealing with the experience of pain. The problem though is, pain is not always a reliable experience. The challenge then becomes when do we trust pain and when do we not? Or maybe a more relevant question is, when is it okay to work through pain? We’ve all experienced the “no pain, no gain” mentality in some form, but this may not always be the best approach depending on your injury.

The short answer is yes, it is okay to work through some pain, but with a bit of common sense. Of course context matters, so we’ll break it down a bit further, but knowing when to push and when to tweak or even hit pause can have a big impact on your recovery.

This is an important concept to address because pain is a complex, individual and multifactorial experience, meaning that everyone experiences it differently and there can be many factors influencing your pain. Pain is also contextual— we (patients and practitioners) seem to accept pain when we’re providing hands-on treatment. I lost track of the number of times someone would ask for more pressure during a massage despite them wincing in pain, or who thought that more would mean a faster recovery. But then when it comes to exercise, we tend to quickly abandon an exercise if the patient experiences any pain with it. So why do we accept pain in some cases, but not others (rhetorical question for the purpose of this blog).

Just know that pain doesn’t always mean damage during the rehab process. The tissue can still be sensitive to loading without resulting in further damage or reinjury. When it comes to pain that develops through overuse or pain that lasts beyond the typical healing time, that’s when pain can be a bit more unreliable, and is still more about sensitivity than damage. Staying active and mobile can help with recovery, provided it is within reason. Being unsure of what is safe or not can certainly cause a dilemma with your recovery - if you back off you might be under-loading yourself, but if you keep going you might be overloading yourself. Neither of these are ideal. But there is a simple analogy you can use to help better gauge your pain and add some clarity to the decision to work through pain during your rehab— the traffic light.

Green Means Go!

In these cases, the pain is mild— I usually consider this to be a self-rated 4/10 or less on the pain scale. This pain generally settles down fairly soon after exercise, or at least within 24 hours, and during the exercise you’re still moving well and feeling confident. This is a good space to work in. The pain is there, but it is not modifying how you perform. You might feel a twinge or ache, but you’re not doing any harm, and your body can handle this. This doesn’t mean that we’re in the clear to go crazy, but it does give an indication that we’re in a good spot with the loading. You should still continue to monitor the pain though, because that leads into…

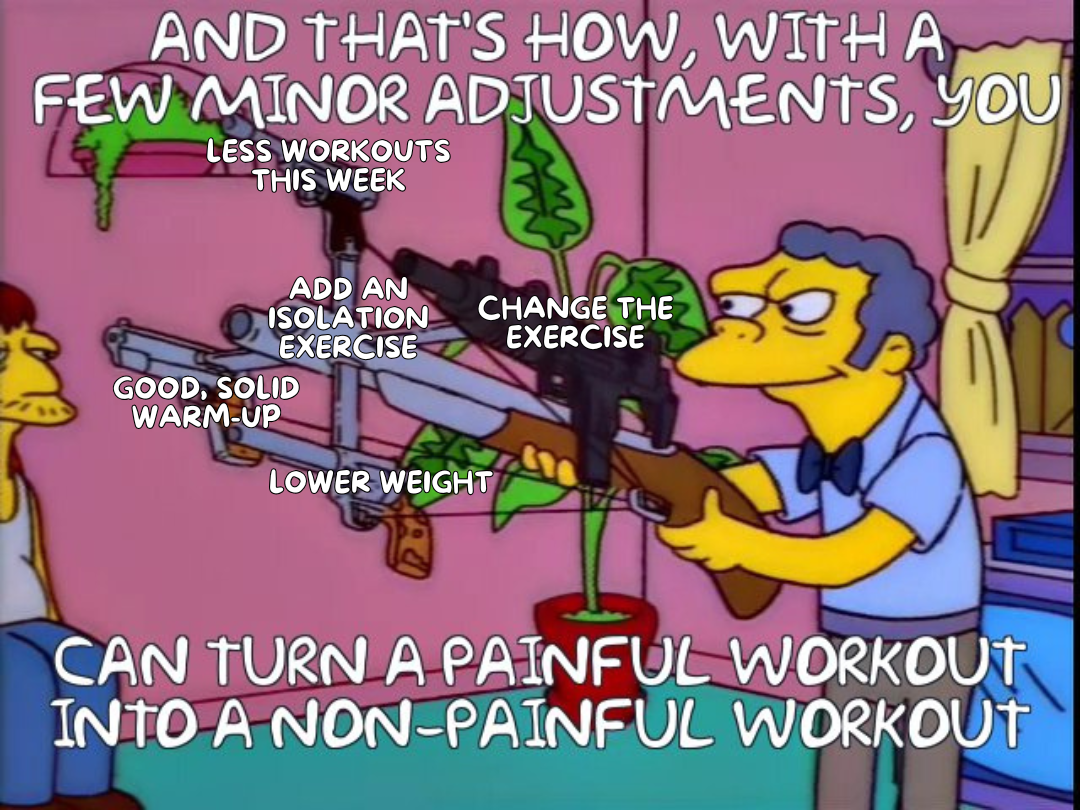

Yellow Means Caution (and Adjust)

This is when the pain increases to a 5/10 or 6/10 on the pain scale, and usually the pain lingers longer than 24 hours before subsiding. Movements might feel a little forced or you might feel guarded, hesitant, deliberate, or cautious during activity. We may not be causing physical damage yet, but we’re certainly starting to push the limits of what the injured tissue can tolerate, and we need to adjust accordingly. The good news is we can still continue some form of exercise, and there are many ways you can adjust to get back into a green light— changing the movement or reducing the weight are just a couple of examples.

Red Means Stop (For Now)

I don’t like having patients stop their exercises, and there are always some unrelated activities they can do to remain active, but sometimes stopping an aggravating exercise is needed. These are cases when the pain is a 7/10 or more; the pain sticks around at that level for longer, or even worsens, and you’re uncomfortable or hesitant to move. This is your cue to rest or scale back to simpler movements that calm the area down, rather than push through and hope for the best because we are at a higher risk of injury. It may seem like we’re losing progress, when really it is just being smart—short-term sacrifice for long-term gain.

It’s okay to feel some pain during the rehab process— tolerable pain doesn’t mean something is injured further. In fact, some studies show it leads to better outcomes than completely avoiding pain (maybe the point when you feel pain is the lower end of the stimulus threshold to cause adaptation, so by avoiding pain you’re not providing adequate stimulation). There’s no need to panic, but it is still worth paying attention to to see how it changes. Maybe it is just a one-off thing because you didn’t sleep very well the night before or maybe it’s a sign that you are not tolerating the exercise well and an adjustment is needed.

Staying active helps the healing process, as long as we are respecting that process and respecting where your body is at.

Ways to Reduce Pain Without Stopping an Activity

One of the most frustrating parts of dealing with an injury is when it takes us away from the things we enjoy- sports, training and daily movement. Sometimes the pain itself forces us to stop, but even when it’s manageable, many people still choose to stop.

One of the most frustrating parts of dealing with an injury is when it takes us away from the things we enjoy- sports, training and daily movement. Sometimes the pain itself forces us to stop, but even when it’s manageable, many people still choose to stop. Hoping the pain goes away on its own, fear of making things worse, fear of more pain, uncertainty, or apprehension are all reasons we stop. This can be especially confusing when the pain only bothers during activity, and not with everyday life.

For the majority of injuries, maintaining some level of activity, even with some pain, is still okay, and in many cases encouraged. We still want to load the painful area so it can adapt, get stronger and become less sensitive. There are many ways to do this, but they mainly fall into three categories.

There are a couple of caveats to this though. Some injuries, such as high-risk bone stress fractures, do require rest. The pain also needs to be at a tolerable level. Pain over a self-reported 7/10 is usually a red light for me as it means the load is too much. It is always important to get a proper assessment so you know whether continuing is safe.

With that said, the three major ways to keep training while managing pain are: movement preparation, movement modification and load adjustment.

Movement Preparation

Sometimes a thorough warm-up or a few targeted exercises to the specific injured/painful area can make a big difference. Increased body temperature, increased blood flow, muscle activation/priming (even though muscles are technically always active unless there’s a nerve injury) and mental preparation all help modulate pain during your session.

Take a runner who feels calf tightness, especially at the start of a run. Exercises like calf stretching, calf raises, double leg hopping, skipping or bounding before the run can help. These exercises prepare the calf muscles for what’s coming and give you way more control over intensity and progression compared to jumping straight into the run.

Movement Modification

Small changes to how you perform an exercise can go a long way for some people when dealing with an injury. The goal here is to train the same muscle groups but in a way that you tolerate more. If someone has shoulder pain when doing lateral raises with their palms down, switching to a more thumbs-up position or bringing their arms forwards a bit can reduce sensitivity. Sometimes it is just specific movements that are irritated. Switching a squat to a leg press machine, or adjusting cadence (step frequency) when running can immediately make training more tolerable.

Load Adjustment

Often the issue isn’t the movement itself — it’s that the load exceeds what your body can currently handle, and usually the simplest step is to temporarily reduce the load. Yes, people dislike lowering weights, but it’s a straightforward and effective strategy. Reducing volume (sets × reps) or training frequency are other options. You’re still doing the activity — just at a level your body can manage right now. Think quality over quantity. For a runner who consistently notices pain getting worse around the 5 km mark, dropping to 4 km and building back up is a perfectly valid approach. Or changing from five runs per week to three, or removing the most stressful run from the schedule.

The key to any of these changes is trial and error. Everyone is different and everyone’s pain experience is different, which makes blanket recommendations tough. The good news is that we have lots of options available to us, which makes the chances of finding something that works very high. The other thing to remember is these changes are temporary. They are short term changes to help bring the pain down while still staying active. Once pain is more under control, then we start progressing back towards our previous levels.

What’s in your cup? The Load-Capacity Framework in Rehab

The load-capacity framework can also guide our treatment plan and what we work on in our rehab. As a reminder, injuries occur when a load on your body exceeds your body’s capacity to handle it. That leaves us with two main ways to help someone- decrease the load or increase their capacity.

The load-capacity framework can also guide our treatment plan and what we work on in our rehab. As a reminder, injuries occur when a load on your body exceeds your body’s capacity to handle it. That leaves us with two main ways to help someone- decrease the load or increase their capacity.

A great analogy for this comes from Greg Lehman when he asks, “what’s in your cup?” Imagine yourself as a cup filled with water. The water represents all the loads you face — not just physical activity, but also work stress, family demands, past injuries, and changes in training or routine. Your cup represents your current capacity to handle these loads. Things like anxiety, lack of sleep, prior beliefs about injury, or self-confidence can all change your cup’s size. Sometimes factors, such as your health status, can both add water and limit your cup’s size.

In rehab, our goal is to either limit the water or build a bigger cup. Limiting water could include adjusting your training program (like decreasing running volume or intensity), managing stress, or changing certain habits. Building a bigger cup might involve strengthening tissues, improving nutrition and hydration, or addressing fears about a specific movement.

Ideally, we can do both at the same time — reduce water and expand the cup. But sometimes we can only tackle one at a time. And sometimes, we can’t change either — reducing work stress might not be realistic, for example. That’s okay. The cup analogy is a way to acknowledge the factors influencing how we feel, and to understand that they’re always changing. Some days it’s like water slowly dripping into a pint glass. Other days, it’s like the Torc Waterfall into a shot glass, and it’s overwhelming.

Recognizing this helps you make informed decisions in training and rehab. A small change — decreasing intensity, taking an extra rest day, or adding one isolation exercise to the painful area — can be enough to manage the load or grow your capacity.

Rehab can be simple but also complex. The simple part is knowing to reduce load temporarily and increase capacity. The complex part is figuring out how, because everyone is different. That complexity might feel intimidating, but it also gives us freedom to find what works best for you.

Reference: Lehman, G. Do our patients need fixing? Or do they need a bigger cup? Online source, 02/05/2018.